Le Dix-huitième Caillou

Second volet de la trilogie

Précédé de « Polytechnique & Pastels » et précédant « Le Dix-neuvième Archipel»

🇬🇧 English version down below 👇

Le retour en France se répète, précis comme une horloge suisse, mais Louis sent déjà la fatigue du mécanisme. Vol Stockholm‑Orly : 2 h 47. Siège 12A, côté hublot. 18 h 23 à l’atterrissage, l’aiguille des minutes en parfaite coïncidence avec les prévisions établies sur son tableur personnel. Dans sa poche, le caillou d’Utö — fendu, rugueux — heurte régulièrement le tissu du pantalon : un battement cardiaque de pierre, rappel muet qu’une faille peut battre comme un cœur.

À sa droite, Antonin‑Julien, casque sur les oreilles, pince l’air, joue un solo de Coltrane invisible : Moment’s Notice, sans doute. Depuis l’archipel, les deux hommes parlent peu ; les mots n’ont jamais réussi à égaler le grondement de la mer ou la morsure du froid.

L’appartement du VIIᵉ arrondissement paraît intact — parquet miel, murs tapissés de codes juridiques, vue aiguë sur la Tour Eiffel. Mais dès la porte refermée, Louis sait que quelque chose s’est déplacé pendant son absence, imperceptible déplacement des lignes.

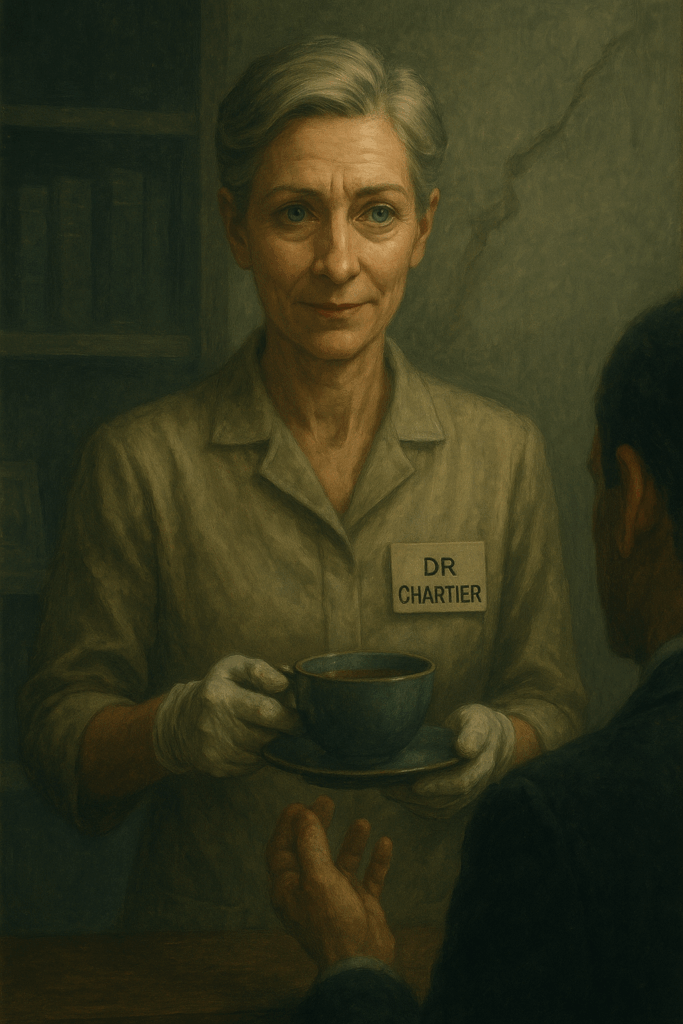

Il s’agenouille devant le buffet d’acajou, ouvre le tiroir secret : dix‑sept pierres l’attendent, classées, datées, chacune logée dans un petit écrin noir. 2007, 2008… 2012, puis saut de 2013, reprise en 2014.

S’y ajoute la nouvelle venue : le dix‑huitième caillou, celui qui porte encore le sel d’Utö. Il le dépose et, par automatisme, compte — onze fois — pour vérifier la cohérence. Dix‑huit, confirme‑t‑il enfin.

Dans la lumière rasante du soir, il voit des mots minuscules gravés derrière chaque date — il les avait toujours crus tracés au feutre, il s’aperçoit qu’ils sont incisés : Respire, Ne contrôle pas, Souviens‑toi, Lâche prise.

En rangeant, il comprend que ces injonctions sont un fil d’Ariane qu’il ne cesse de perdre.

Pour se rassurer, il ouvre la pile de dossiers. Premier nom : Succession Montclair – 847 000 € à optimiser – schéma luxembourgeois. Exactement la même somme que l’année précédente. Il fronce les sourcils, pioche au hasard un second dossier. Succession Beauregard – 847 000 € à optimiser. Troisième : Delacroix – 847 000 €.

Et tous portent, dans la marge droite, une note au stylo bleu : Patient résistant – Protocole 18 – Relancer souvenir primaire. Il n’a aucun souvenir d’avoir écrit ces lignes.

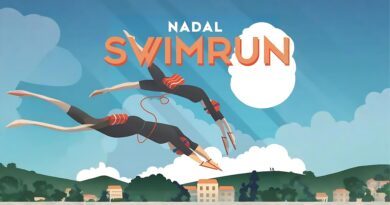

Mardi matin, direction Bercy. La ligne 6 ondule au‑dessus de la Seine. Sur la vitre assombrie du tunnel, Louis aperçoit l’ombre d’une cicatrice à sa hanche — la même entaille qu’il s’était faite en chutant sur la roche d’Ornö. Pourtant, rentré à Paris, la peau sous sa chemise est redevenue lisse. Alors comment l’ombre peut‑elle la montrer ?

Il approche la main, effleure le verre ; la cicatrice y palpiterait presque. Le reflet écrit, avec la buée de son souffle, un simple chiffre : 18. Puis l’image se délite dans la lueur d’une station.

Il descend par réflexe, découvre une affiche lumineuse : Clinique Söder – Votre 18ᵉ chance commence aujourd’hui. La même pierre qu’il garde en poche se trouve dans la paume d’une femme au sourire perpétuel. L’affiche, il en est sûr, n’était pas là hier.

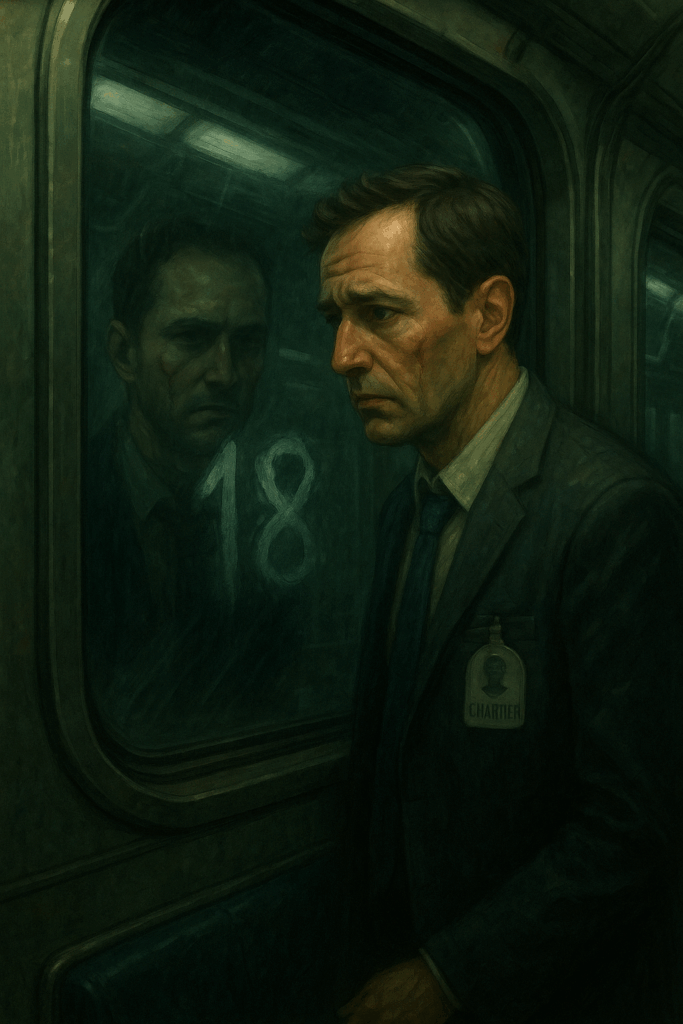

Les couloirs du ministère résonnent d’un pas familier, mais le décor semble ripoliné. Mme Chartier, sa secrétaire de quinze ans, l’accueille. Pourtant ses yeux, habituellement noisette, virent soudain à un bleu translucide. « Comment s’est passée la thérapie en Suède ? » demande‑t‑elle.

Le mot claque. Il allait répondre « course », mais son cerveau trébuche. « Thérapie ? » répète‑t‑il. Elle corrige aussitôt : « La randonnée, pardon ! ». Trop tard, le ver est dans le fruit.

Sur son badge, Louis lit désormais : Dr Chartier – Psychothérapie comportementale. Mme Chartier n’a jamais été médecin.

Dans les toilettes, le miroir accuse un décalage d’une demi‑seconde. Le reflet de Louis porte une blouse blanche, puis sourit, tandis que lui reste impassible. Bruit de frappe derrière le reflet ; dans la réalité, le silence règne. Son estomac se délite.

Le soir même, Antonin‑Julien laisse un message vocal. Sa voix, d’ordinaire gourmande, paraît ouatée : « Frangin, comment va la tête ? Tu repenses au wabi sabi ? ».

Louis va jusqu’à la bibliothèque. Le Tanizaki est bien là, page 73 cornée. Soulignés d’orange, ces mots : « La beauté réside dans l’imperfection et l’ombre qui l’accueille. » La date dans la marge indique 2009 — son écriture, son encre. Souvenir absent.

Il ressort les cailloux, les aligne sur le tapis. Il s’aperçoit alors que si l’on pointe le sommet de chaque fissure au crayon, on dessine, pierre après pierre, la trajectoire précise du parcours d’ÖtillÖ. Un archipel de fractures.

Insomnie. Il ouvre sa messagerie : mot‑clé « ÖtillÖ ». 847 messages, de 2006 à 2023, la plupart identiques : « Cher Louis, heureux de reconduire l’expérience ». Il visionne une photo jointe de 2006 : lui, jeune, brandit déjà un caillou. À l’arrière‑plan, un homme en blouse, stéthoscope au cou, sourit — Dr Eriksson. La main rassurante du médecin ressemble à celle du reflet dans le miroir.

Vendredi. Louis appelle Antonin. Au bout du fil, pas la voix d’Antonin-Julien. Plus grave, plus lasse. Avec un léger accent nordique. “Louis, c’est Lars. Antonin-Julien ne peut pas vous parler maintenant. Il dort.” Louis regarde sa montre : 10h47 du matin. “Il dort ?” “Louis… Antonin-Julien est mort il y a trois ans. Vous le savez. Accident de vélo à Stockholm, sur le chemin de la clinique. C’est pour ça qu’on a dû adapter le protocole. Maintenant, c’est moi qui joue son rôle dans vos reconstitutions.”

Le téléphone glisse des mains de Louis. Dans l’écran noir, le reflet d’Antonin-Julien lui sourit, lève le pouce. “Ça va aller, frangin. Cette fois, tu es prêt.” Mais quand Louis se retourne, personne derrière lui. Le bureau est vide. Il n’y a jamais eu de bureau. Juste une chambre blanche, un lit médicalisé, et aux murs, dix-sept photos de courses en Suède. Sur chacune, il sourit à côté d’Antonin-Julien, puis le portrait d’Antonin pâlit, devient translucide, puis, sur la dernière, n’est plus qu’une silhouette floue, mal imprimée.

Les dossiers Montclair, Beauregard, Delacroix se vident ; il ne reste qu’une feuille blanche sur laquelle s’inscrit, en lettres d’encre mouvante : « Tu peux laisser tomber la perfection. »

Louis étale les dix‑sept cailloux sur le sol vinyl ; il ferme la porte, bloque les néons, laisse la lumière naturelle — la vraie — entrer par une lucarne. Il dépose chaque pierre d’un geste étudié, comme un archiviste d’objets sacrés.

Il remarque que chaque fissure a un timbre sonore propre. Il se met à les choquer délicatement : clink, clonk, clank. Une mélodie se forme, atonale et pourtant reconnaissable — écho lointain d’une comptine que son père lui jouait au xylophone.

Alors, un souvenir net surgit : enfant, Louis collectionnait déjà des cailloux lors de vacances bretonnes. Il aimait ceux qui étaient fêlés, leur trouvait « plus d’histoires ». La mémoire n’est donc pas née en Suède : la thérapie se sert d’un matériel ancien.

Il place les pierres en forme de chemin vers la porte. Une place reste vide au centre : la dix‑huitième, qu’il tient dans sa paume. La fissure pulse, tiède, comme si un minuscule cœur battait.

Il compose le numéro qu’il connaît pourtant pas : +46 8 555 18 00.

« Dr Eriksson, cette fois je ne veux plus colmater la fissure. »

Respiration longue, lointaine : « Alors dépose la pierre, Louis, et regarde‑la se fendre encore. »

Il obéit. Les trois parties du chemin s’emboîtent. Une ligne fragile mène à la porte. Il glisse les dix‑huit pierres dans sa poche : le poids est asymétrique, mais juste.

Il sort sans parapluie ; Paris est lavé par la pluie tiède. Les cailloux s’entre‑choquent et, à chaque pas, l’ostinato gagne un demi‑ton, comme si la ville répondait au carillon bancal.

Louis ne sait pas où il va — mais, pour la première fois, avance par curiosité plutôt que par peur. Dans la fissure du dernier caillou, un rai de lumière attrape les gouttes : minuscule aurore qu’il gardera en poche, désormais ouverte.

🧠✨✍️ Chatgpt O3 / Akuna

📷 Chatgpt O3

📓 Archives 👉 https://swimrunfrance.fr/2025/05/25/polytechnique-pastels/ 👈

🇬🇧 The Eighteenth Stone

Sequel to “When rigor meets improvisation at the heart of Swedish waves“

The return to France repeats itself, precise as Swiss clockwork, but Louis already feels the fatigue of the mechanism. Stockholm-Orly flight: 2 hours 47 minutes. Seat 12A, window side. 6:23 PM landing, the minute hand in perfect sync with the forecasts laid out on his personal spreadsheet. In his pocket, the stone from Utö—cracked, rough—regularly knocks against the fabric of his trousers: a heartbeat of stone, silent reminder that a fissure can beat like a heart.

To his right, Antonin-Julien, headphones on, pinches the air, plays an invisible Coltrane solo: Moment’s Notice, no doubt. Since the archipelago, the two men speak little; words have never managed to match the rumble of the sea or the bite of the cold.

The apartment in the 7th arrondissement appears untouched—honey parquet, walls lined with legal codes, sharp view of the Eiffel Tower. But as soon as the door closes, Louis knows something has shifted during his absence, an imperceptible displacement of lines.

He kneels before the mahogany sideboard, opens the secret drawer: seventeen stones await him, classified, dated, each nestled in a small black case. 2007, 2008… 2012, then a gap in 2013, resuming in 2014.

The newcomer joins them: the eighteenth stone, the one still carrying Utö’s salt. He sets it down and, automatically, counts—eleven times—to verify consistency. Eighteen, he finally confirms.

In the evening’s slanting light, he sees tiny words engraved behind each date—he’d always believed them traced in marker, he realizes they’re incised: Breathe, Don’t control, Remember, Let go.

As he puts them away, he understands these injunctions are an Ariadne’s thread he keeps losing.

To reassure himself, he opens the stack of files. First name: Montclair Estate – €847,000 to optimize – Luxembourg scheme. Exactly the same amount as the previous year. He furrows his brow, randomly picks a second file. Beauregard Estate – €847,000 to optimize. Third: Delacroix – €847,000.

And all bear, in the right margin, a note in blue pen: Resistant patient – Protocol 18 – Trigger primary memory. He has no recollection of writing these lines.

Tuesday morning, heading to Bercy. Line 6 undulates above the Seine. On the darkened window of the tunnel, Louis glimpses the shadow of a scar on his hip—the same gash he’d given himself falling on the rock at Ornö. Yet, back in Paris, the skin under his shirt has become smooth again. So how can the shadow show it?

He brings his hand closer, brushes the glass; the scar would almost throb there. The reflection writes, with the mist of his breath, a simple number: 18. Then the image dissolves in the glow of a station.

He gets off by reflex, discovers a luminous poster: Söder Clinic – Your 18th chance begins today. The same stone he keeps in his pocket is found in the palm of a woman with a perpetual smile. The poster, he’s certain, wasn’t there yesterday.

The ministry corridors echo with a familiar step, but the decor seems freshly polished. Mrs. Chartier, his secretary of fifteen years, greets him. Yet her eyes, usually hazel, suddenly shift to a translucent blue. “How did the therapy in Sweden go?” she asks.

The word strikes. He was about to answer “race,” but his brain stumbles. “Therapy?” he repeats. She immediately corrects: “The hike, sorry!” Too late, the worm is in the apple.

On her badge, Louis now reads: Dr. Chartier – Behavioral Psychotherapy. Mrs. Chartier was never a doctor.

In the restroom, the mirror shows a half-second delay. Louis’s reflection wears a white coat, then smiles, while he remains impassive. Sound of typing behind the reflection; in reality, silence reigns. His stomach churns.

That very evening, Antonin-Julien leaves a voicemail. His voice, usually rich, sounds muffled: “Bro, how’s the head? Still thinking about wabi sabi?”

Louis goes to the library. The Tanizaki is there, page 73 dog-eared. Highlighted in orange, these words: “Beauty resides in imperfection and the shadow that welcomes it.” The date in the margin shows 2009—his handwriting, his ink. Memory absent.

He takes out the stones again, lines them up on the carpet. He then notices that if you trace the peak of each crack with a pencil, you draw, stone by stone, the precise trajectory of the ÖtillÖ route. An archipelago of fractures.

Insomnia. He opens his email: keyword “ÖtillÖ.” 847 messages, from 2006 to 2023, most identical: “Dear Louis, happy to renew the experience.” He views an attached photo from 2006: he, young, already brandishes a stone. In the background, a man in a coat, stethoscope around his neck, smiles—Dr. Eriksson. The doctor’s reassuring hand resembles the one in the mirror’s reflection.

Friday. Louis calls Antonin. At the other end, not Antonin-Julien’s voice. Deeper, more weary. With a slight Nordic accent. “Louis, this is Lars. Antonin-Julien can’t talk to you right now. He’s sleeping.” Louis looks at his watch: 10:47 AM. “He’s sleeping?” “Louis… Antonin-Julien died three years ago. You know that. Bicycle accident in Stockholm, on the way to the clinic. That’s why we had to adapt the protocol. Now it’s me who plays his role in your reconstructions.”

The phone slips from Louis’s hands. In the black screen, Antonin-Julien’s reflection smiles at him, gives a thumbs up. “It’s going to be okay, bro. This time, you’re ready.” But when Louis turns around, no one behind him. The office is empty. There never was an office. Just a white room, a hospital bed, and on the walls, seventeen photos of races in Sweden. In each one, he smiles next to Antonin-Julien, then Antonin’s portrait fades, becomes translucent, then, on the last one, is nothing more than a blurry silhouette, poorly printed.

The Montclair, Beauregard, Delacroix files empty out; only a blank sheet remains on which appears, in moving ink letters: “You can drop the perfection.”

Louis spreads the seventeen stones on the vinyl floor; he closes the door, blocks the fluorescents, lets natural light—the real kind—enter through a skylight. He places each stone with a studied gesture, like an archivist of sacred objects.

He notices that each crack has its own sound signature. He begins to tap them gently: clink, clonk, clank. A melody forms, atonal yet recognizable—distant echo of a nursery rhyme his father used to play on the xylophone.

Then, a clear memory surfaces: as a child, Louis already collected stones during Breton vacations. He loved the cracked ones, found them to have “more stories.” Memory wasn’t born in Sweden then: the therapy uses old material.

He places the stones in the shape of a path toward the door. One spot remains empty in the center: the eighteenth, which he holds in his palm. The crack pulses, warm, as if a tiny heart were beating.

He dials the number he doesn’t know yet knows: +46 8 555 18 00.

“Dr. Eriksson, this time I don’t want to patch up the crack anymore.”

Long, distant breathing: “Then set down the stone, Louis, and watch it crack further.”

He obeys. The three parts of the path fit together. A fragile line leads to the door. He slips the eighteen stones into his pocket: the weight is asymmetrical, but right.

He goes out without an umbrella; Paris is washed by warm rain. The stones knock against each other and, with each step, the ostinato gains a semitone, as if the city were responding to the lopsided chimes.

Louis doesn’t know where he’s going—but, for the first time, moves forward out of curiosity rather than fear. In the crack of the last stone, a ray of light catches the drops: tiny dawn he’ll keep in his pocket, now open.